I was surprised to find both in my reading of Genesis and in subsequent scholarly research how inconclusive the text is regarding why Cain’s offering is rejected. This seems to be an integral aspect of the story, because one of the great lessons to be learned is how to please God and the lack of an explicit discussion regarding what God seeks in the offerings. One common theory about why God rejected Cain’s offering is because of its bloodless nature. However, it seems unlikely that God give a preference for live offerings over bloodless offerings for a few reasons. First, God seems to show great reverence for the land when he assigns Adam to “till the ground from whence he was taken” (Genesis 3:23). Instead, it seems likely that the greater use of adjectives referring to Abel’s offering distinguishes it implicitly from Cain’s. Abel “brought of the firstlings of his flock and of the fat thereof” (Genesis 4:4). However, “Cain brought of the fruit of the ground an offering” (Genesis 4:3). Some scholars argue that “by offering the firstborn Abel signified that he recognized God as the Author and Owner of Life,” and the accompanying descriptor of Cain’s offering as being of the ‘firstfruits’ is intentionally missing (Waltke 368). While this explanation is certainly not definitive, it makes greater contextual sense to me instead of the ‘bloodless’ theory that many assume. It seems likely that if the ‘bloodless’ hypothesis were true, the author would have emphasized the blood in its description of Abel’s offering. There were also striking parallels between Cain and Abel and the excerpt from the Jungle Book. In the final story with the Tiger, the Tiger “killed the buck, and thou hast let Death loose in the Jungle” (57). The Tiger is singled out for committing the first murder of the animal kingdom, much like Cain. There is even a ‘scar’ imposed on the animal kingdoms, with the “black stripes upon his flank and his side” resembling the marks left because of Cain’s murder (58).

|

| tiger |

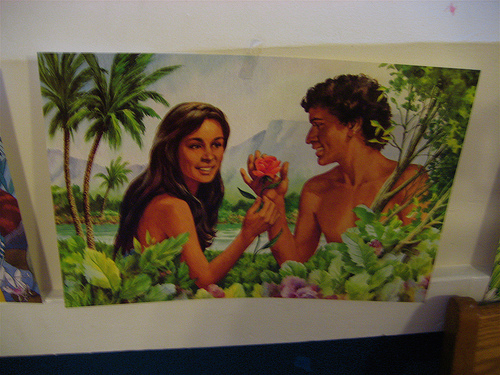

Paradise Lost offers some interesting commentary about the Tree of Knowledge. Eve provides two reasons why she should not eat from the Tree of Knowledge. Later in her conversation with Satan, she claims that “God so commanded” for her to not eat from the tree (652). However, earlier in the conversation, the speaker reveals his voice and refers to the tree as the “root of all our woe” (645). This analysis of why the tree should not be eaten utilizes a consequentialist justification. While this provides an interesting interpretation for why the tree should not be eaten from, some implicit anthropocentric analysis is also given regarding the tree. In the face of the tree, many animals saw the tree as they “longing and envying stood, but could not reach” (593). I am not claiming that this is anthropocentric because it underestimates the physical capabilities of the animals. Rather, this analysis seems to imply that animals do not have the choice to fall outside of God’s approval because they were never within the purview of God’s watch in the first place.

|

| adam and even posing with the tree of knowledge |

Bruce Waltke. “Cain and His Offering”. Westminster Theological Journal 48 (1986). Page 368.